FRANCE - A spacecraft launched last year will slingshot back around Earth and the Moon next month in a high-stakes, world-first manoeuvre as it pinballs its way through the Solar System to Jupiter.

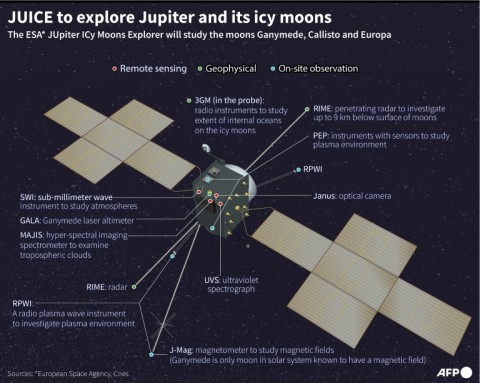

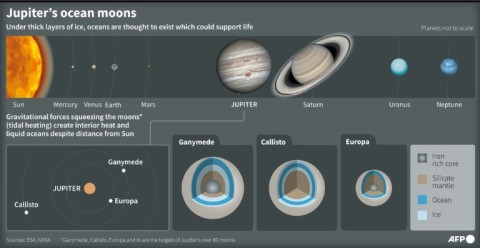

The European Space Agency's Juice probe blasted off in April 2023 on a mission to discover whether Jupiter's icy moons Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa are capable of hosting extra-terrestrial life in their vast, hidden oceans.

The uncrewed six-tonne spacecraft is currently 10 million kilometres (six million miles) from Earth.

But it will fly back past the Moon then Earth on August 19-20, using their gravity boosts to save fuel on its winding, eight-year odyssey to Jupiter.

Staff at the ESA's space operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany began preparing for the complicated manoeuvre this week.

Juice is expected to arrive at Jupiter's system in July 2031.

It will take the scenic route. NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft is scheduled to launch this October yet beat Juice to Jupiter's moons by a year.

- Long and winding road -

Juice is taking the long way round in part because the Ariane 5 rocket used to launch the mission was not powerful enough for a straight shot to Jupiter, which is roughly 800 million kilometres away.

Without an enormous rocket, sending Juice straight to Jupiter would require 60 tonnes of onboard propellant -- and Juice has just three tonnes, according to the ESA.

"The only solution is to use gravitational assists," Arnaud Boutonnet, the ESA's head of analysis for the mission, told AFP.

By flying close to planets, spacecrafts can take advantage of their gravitational pull, which can change its course, speed it up or slow it down.

Many other space missions have used planets for gravity boosts, but next month's Earth-Moon flyby will be a "world first", the ESA said.

It will be the first "double gravity assist manoeuvre" using boosts from two worlds in succession, the agency said.

Juice will cross 750 kilometres above the Moon on August 19, before shooting past our home planet the following day.

The probe will leave Earth at a speed of "3.3 kilometres a second - instead of three kilometres if we had not added the Moon", Boutonnet said.

As Juice whizzes past Earth and the Moon, it will use the opportunity to snap photos and test out its many instruments.

Down on Earth, some will be taking photos right back. Some lucky amateur sky gazers, armed with telescopes or powerful binoculars, may even be able to spot Juice as it passes over Southeast Asia.

- 'Plate of spaghetti' -

The move has been carefully calculated for years, but it will be no walk in the park.

"We are aiming for a mouse hole," Boutonnet emphasised.

The slightest error during its slingshot around the Moon would be amplified by Earth's gravity, potentially creating a small risk that the spacecraft could enter and burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

The team on the ground will be closely observing the spacecraft - and have 12-18 hours to calculate and adjust its trajectory if needed, Boutonnet said.

He mostly feared a scenario in which the amount of course corrections needed would erase the gains from the double-world slingshot, meaning they would be "doing all this for nothing".

If all goes well, Juice will head back out into interplanetary space - for a little while at least.

It will first head to Venus for another boost in 2025.

Juice will even fly past Earth twice more - once in 2026, then a final time in 2029 before finally setting off towards Jupiter.

Then comes the really tricky part.

Once Juice arrives at Jupiter, it will use a whopping 35 gravitational assists as its bounces around the planet's ocean moons.

During this phase, the probe's trajectory looks like "a real plate of spaghetti", Boutonnet said.

"What we're doing with the Earth-Moon system is a joke in comparison," he added.

By Juliette Collen