Dishes of spit-roasted lamb were served and the sound of electric guitars echoed across the pink Saharan dunes towards the Air Mountains.

"It's like playing at home," said musician Oumara Moctar.

The desert, he said, "is where we were born, where we grew up, and reminds us of where we come from."

One of the biggest cultural events in the Sahel region, the Aïr Festival returned last week, bringing the songs, dances and oral traditions of the nomadic Tuareg culture to an audience of thousands -- and a burst of hope for jihadist-scarred Niger.

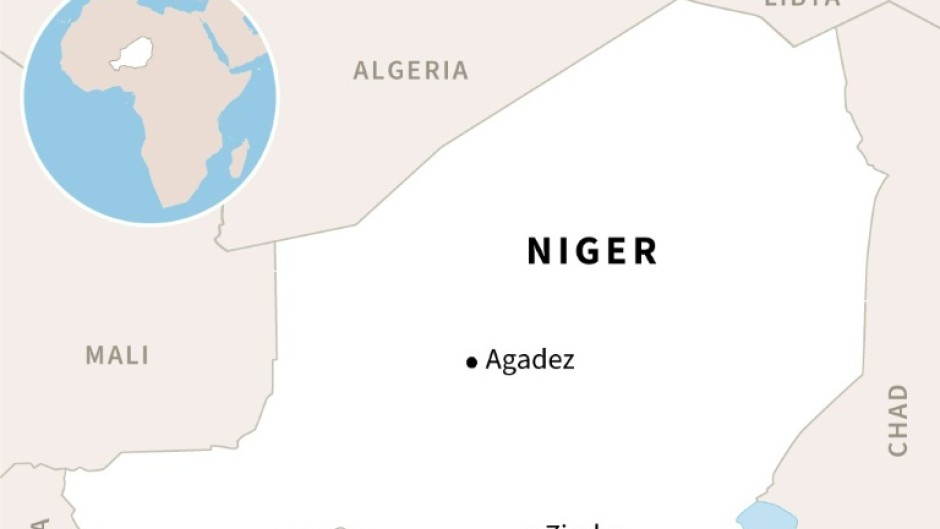

The eagerly-awaited three-day party unfolded in Iferouane, an oasis sandwiched between desert and mountains 1,200 kilometres from the Nigerien capital Niamey.

Some 5,000 people, many of them local VIPs and a few foreigners, replaced the desert's usual calm with a ballet of 4x4s whipping up plumes of dust.

After attending concerts and beauty pageants, festival-goers spent long hours reclining on mats where, in between rounds of tea, discussion ranged from the merits of Toyota pick-up trucks to barely-concealed regionalism.

"Tuareg culture, in a nutshell," smiled young Iferouane resident Mohamed Bouhamid.

If not for the pervasive presence of troops to provide security, this scene could have taken place some two decades ago.

The festival, launched in 2001, last took place in 2020. In its prime, well-heeled European visitors beat a path to Niger and neighbouring Mali, and men who are now rebel chiefs worked as tourist guides.

An airline linked Paris directly to Agadez in Niger and to Gao and Kidal in Mali. For many years, the Paris-Dakar rally raced through the desert.

Memories of this halcyon time persist today, despite the two jihadist insurgencies that beset Niger, and its chronic poverty -- it is ranked the world's poorest country by the benchmark of the UN Human Deveopment Index.

- 'Hysteria' -

After six French citizens were killed just outside Niamey in 2020, France -- previously the main source of tourists -- declared Niger a "red zone" and recommended travel there be avoided.

For those wishing to visit the festival in Iferouane, the French authorities recommended postponement.

Deputy mayor Hamadi Yahaya denounced "these embassies" that "have sparked hysteria" despite the conflict being more than 1,000 kms away from Iferouane.

Mayor El Gondj Ahmed or "the Honorable" as he is called locally, repeatedly said "everything is secure here."

In addition to the troops, dozens of Ishumars -- a name given to former rebels -- "have been deployed in the surrounding desert", said Rhissa Ag Boula, a rebel leader who now serves as an adviser to Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum.

At nearby Chiriet, the Ishumars' trucks bearing recognisable white flags remained at a discreet distance. They flanked a rowdy race between some 80 drivers speeding through the sand.

Rocco Rava, an Italian who manages a tour agency called Societe de Voyages Sahariens (SVS), had returned to the region for the first time in 15 years.

He grew up in the regional capital Agadez where he developed his tourism business before moving to neighbouring Chad when the "turbulence" began in Niger.

- Tourism and machine guns -

"There is a strong demand," he said, explaining he had come to Iferouane to check out the possibility of bringing tourists back.

But the situation is paradoxical, he said: "If it's really secure, then tourists ask us why we need to have a military escort."

Niger requires all Westerners travelling to the desert to be accompanied by an armed escort, for which they must pay.

"In what country in the world do you do tourism with a machine gun in front of you and another one behind you?" asked another tourism professional, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

People must accept that the "before" times are over, said the president of Iferouane's artisan collective, Kader Hamadede, who has been making jewellery for three decades.

"The tourism we'll have from now on will always involve the military, and I don't know if tourists are interested in that."

Many local people were downbeat about prospects for a better life and some saw migration or working in the illegal gold mines dotting the Sahara as their only hope.

"There's nothing more to do here," said 22-year-old Mohamed Bouamid, who hopes to make his fortune with a four-month stint in the gold business.