TEGUCIGALPA - Nestled in the mountains of central Honduras, the "El Encanto" coffee farm is tackling this year's harvest with half the pickers it needs.

In Costa Rica's Central Valley, the "Hersaca Tres Marias" farm faces a similar dilemma. The seasonal laborers both rely on are among the thousands to have abandoned Central American shores in search of a better life elsewhere.

"Many of our coffee pickers now go to the United States, to other countries, for a lack of opportunities" at home, farmer Selvin Marquez, 34, told AFP in Siguatepeque, some 90 kilometers (56 miles) north of the Honduran capital Tegucigalpa.

Coffee growers like Marquez are at their wit's end, watching the fruit of their labors, and their incomes, shrivel up.

Marquez planted five hectares of coffee that now needs harvesting. But he has only 20 of the 40 pickers he needs.

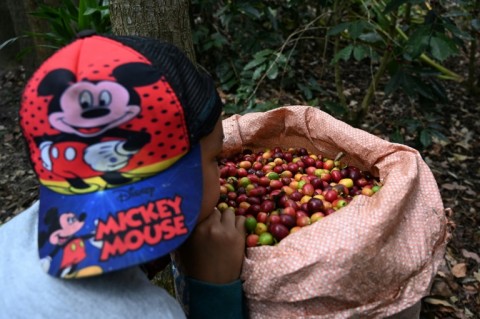

One of them is Jose Samuel Hernandez, 34, in the fields with his wife Esly Mejia, 24, daughter Alexa, two, and sister-in-law Gleny, 20.

Every hand counts, and even Alexa helps pick some of the low-hanging fruit while playing with a dusty teddy bear.

The family cuts 182 kilograms (402 pounds) in eight hours and receives the equivalent of $0.10 per kilo.

An "insufficient" income, said Hernandez, whose basic monthly expenses are the equivalent of $567 a month.

But he has little choice. A security guard for the rest of the year, a job at which he earns $429 per month, he took the day off to join his family coffee picking.

Hernandez said many of his friends have left Honduras. He, too, has thought of packing up. "But what will happen to my family?"

Fleeing poverty

The authorities in Honduras estimate that 1,000 of its 9.5 million citizens leave every day with the hopes of making it to the United States for a chance at the "American dream."

They seek to escape rampant poverty and violence in one of the world's top ten coffee producing countries.

Some 250,000 hectares of coffee plantations are shared between more than 100,000 mainly small-scale producers.

The industry generates a million jobs and accounts for about 38 percent of Honduras' agricultural GDP, according to the Honduran Institute of Coffee.

In the 2021/22 season, the country exported coffee worth some $1.4 billion.

Costa Rica, too, is a major producer, and similarly affected by emigration. But here the problem is slightly different.

The comparatively stable country relies heavily on hired hands from neighboring Nicaragua for its coffee picking.

But since a clampdown on critics and the opposition following 2018 protests that were violently put down, more and more Nicaraguans are leaving for shores further afield.

Managua does not provide emigration data, but more than 164,000 Nicaraguans were intercepted at the US border in the 2022 fiscal year -- a three-fold increase in 12 months, according to American customs authorities.

'They have left'

Nicolas Torres, 70, is one of the shrinking number of Nicaraguan laborers to have returned this year to the farm Hersaca Tres Marias in the region of Birri, some 37 kilometers north of the capital San Jose.

With his deeply tanned hands, he caresses the grains.

"I grew up in coffee," he told AFP, picking non-stop. "This is one of the good jobs I have always done."

Torres laments that in his own country, finding work is difficult and "a lot of pressure in the country... makes us emigrate."

Costa Rica boasts some 94,000 hectares of coffee plantations that employ about 25,000 pickers every season -- mostly Nicaraguans but also Panamanians and locals, according to Bilbia Gonzalez of the country's Coffee Institute.

The pickers earn about $0.15 per kilo.

Migrant workers from Nicaragua, a country of nearly seven million people, are "extremely important" for Costa Rica, which exported $337.8 million dollars in coffee in 2021/22, said Gonzalez.

Yet, "there are few Nicaraguans" to do the work, added Geovanny Montero, manager at Hersaca Tres Marias. "They have left for the United States."

Last year, the farm hosted 70 pickers, said Montero. This year, there are 50 -- a reduction he calculates will result in a five percent smaller harvest.

"That is a lot of money," Montero lamented as he pointed to fallen coffee fruit on the ground.